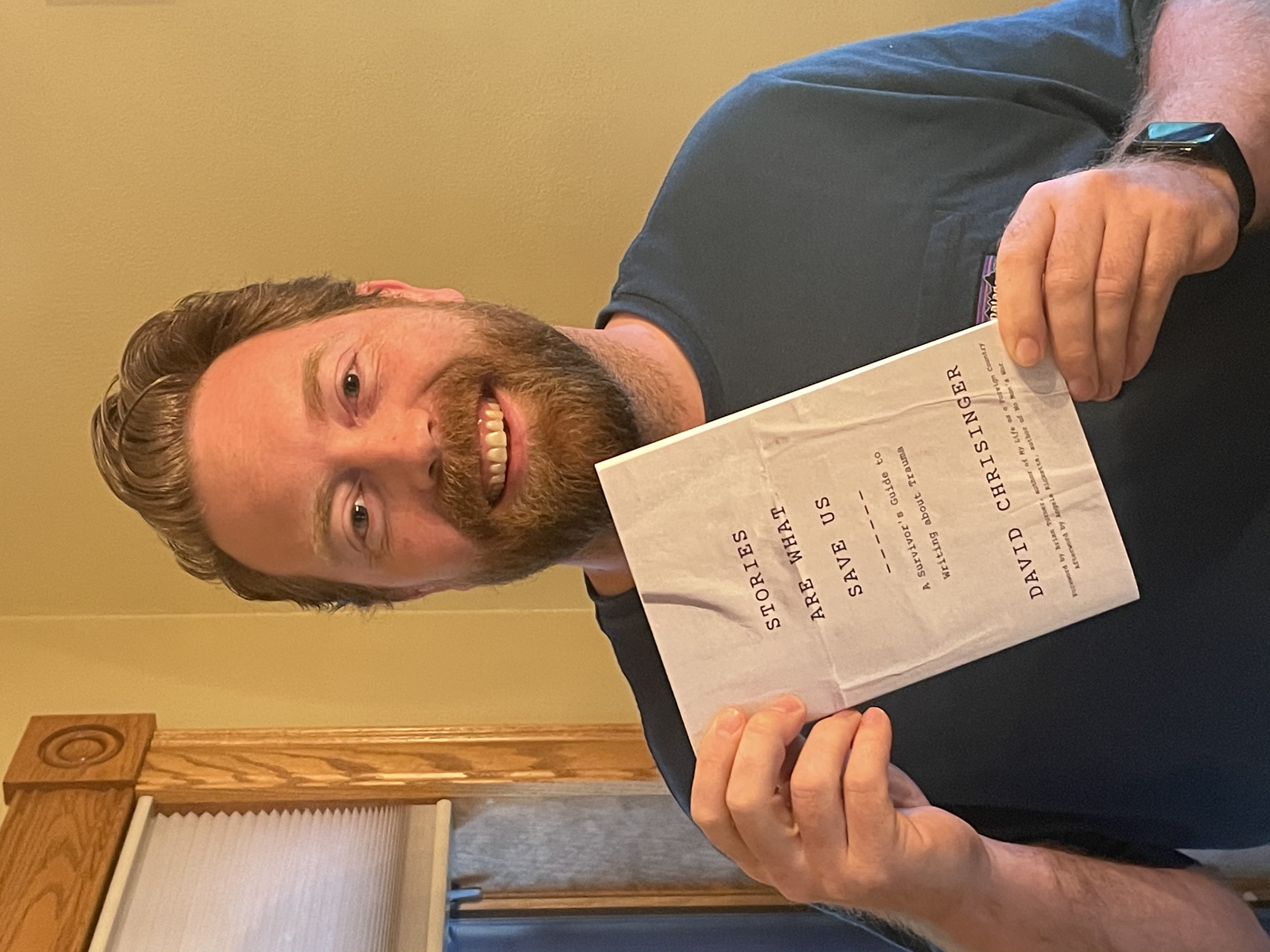

Q&A: David Chrisinger on His New Book, “Stories Are What Save Us”

David Chrisinger, who leads the Harris Writing Program, is now out with a new book, Stories Are What Save Us: A Survivor’s Guide to Writing about Trauma, which is part writing manual, part memoir, and part guidebook for how to navigate issues of trauma in personal narratives. Drawing on personal experience, technical knowhow, and years in the classroom, David Chrisinger’s book has something for writers of all stripes. We sat down with David to learn more about the book:

Why did you decide to write a book about writing and trauma?

I have a confession to make: I didn’t set out to write a book about writing and trauma. What I wanted to write was a memoir of my journey to uncover the truth about what my grandfather experienced fighting in the Pacific during World War II. Some of that story is included in Stories Are What Save Us, so I won’t ruin it for anyone, but suffice it to say that I just couldn’t figure out a way to turn what I had into a whole book—a book that someone who didn’t know me would be interested in reading. A much shorter version of the story was published in the New York Times back in January 2019.

I thought I was done with that project. But later I was talking to my editor at Johns Hopkins University Press about the second edition of my book on writing public policy (due out February 1, 2022), and for whatever reason, I asked him what he thought about a book of essays that would essentially be a guide to writing about trauma, like I had done in the article about my grandfather. My editor was intrigued, so I wrote an introduction and a long summary of what the book would look like, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Fortunately, I had years of teaching experiences that taught me dozens of lessons about writing—and about people, too—and I knew that if I could figure out how to tell those stories and show people how to avoid all the missteps I’ve taken over the years, that would be a book worth writing.

The foreword to this book – written by Brian Turner – describes what you’ve done as a writer’s guidebook, a memoir, and a teacher’s handbook. You describe it yourself as an atonement. Which is right?

When I sat down to write the introduction to this book for my proposal to the publisher, I kept coming back to that word: Atonement. A reparation. A way to make things right. When I started teaching storytelling to military veterans, I didn’t fully appreciate what it meant for them to open themselves up to me, a civilian no less. I knew how to tell good stories, I knew how to edit mediocre stories to make them good, and I knew how to teach others how to do the same. What I didn’t know how to do was make sense of the emotions that were stirred up—both in my students and in myself. It’s one thing to write a dispassionate policy brief, and it’s quite another to help someone understand what it’s like to go through something that makes them wish they’d never been born in the first place. So I read more, and I earned several certifications, and I interviewed experts, and I figured out ways of helping writers process what they’ve been through as they write.

If you’re a budding memoirist, this book shows you everything you need to know to get started and to write something you can be proud of. If you’re a teacher of writing, you can feel free to steal my exercises and lessons so that your students can benefit from them. And if you’re a lover of good storytelling, I’d like to think you’ll enjoy the stories I’ve told.

You’ve worked closely with veterans and service members at The War Horse, teaching them to tell their stories from the front lines. Is this book just about war?

No, not at all: It’s a book about storytelling and how finding a way to tell your story of trauma—whatever form that takes—and transformation can not only help you feel more whole, but it can also help connect you with others and lead to greater understanding, even from readers who would have otherwise been unable to imagine what you’ve been through.

Whatever the source of our traumas, I’ve found that they manifest themselves in our lives in strikingly similar ways. Much of my work has been with military veterans and their families, though I’ve also used the stories, structures, and strategies included in this book to teach writing to refugees, rape survivors, and those who have lost children or other close relatives. In my classes, and in this book, I stress again and again that there is no “hierarchy of suffering” when it comes to trauma. What that means is that your life’s traumas are not greater or more worthy of attention than mine, and vice versa. There is no point to such a hierarchy because, as Holocaust survivor and noted psychologist Viktor Frankl says:

a man’s suffering is similar to the behavior of a gas. If a certain quantity of gas is pumped into an empty chamber, it will fill the chamber completely and evenly, no matter how big the chamber. Thus suffering completely fills the human soul and conscious mind, no matter whether the suffering is great or little.

The book is subtitled “A Survivor’s Guide to Writing about Trauma,” and it weaves in stories from your own life and family. Why was it important to you that you share your stories, as well?

There are two reasons. First, and probably most importantly, I believe that as a teacher I should not ask my students to do anything that I myself am not willing to do. When I ask my students to write about painful and traumatic experiences in their lives, that is an incredibly vulnerable position for them to be in. So I do it first. I put myself—warts and all. I show them that there is tremendous courage required to be vulnerable but that all the benefits far outweigh the costs.

Second, I’ve found storytelling to be the most effective and impactful teaching strategy out there. I could have written a very straight-forward, step-by-step instructional guide for how to tell a story, but I’m not convinced anyone would want to read that. When I teach, on the other hand, with my stories of ups and downs, traumas and transformations, students and readers are not only entertained, but they also connect better to the lessons. They can see themselves in the stories I tell, and then with a little instruction for how to do what I just did, readers can walk away feeling like they found a formula for producing those same reactions and connections with their own stories.

Why write?

Because someday I’ll be gone, and I don’t want my kids or my grandkids to have to travel halfway around the world — like I did — to find out what I’ve been through and how I became who I am. (There’s more in the book about that journey, if you’re interested.) And because I want to know other people’s stories, too. The best way I’ve found to have a real conversation like that is to start it yourself.

What are you reading now? Do you have any recommendations for the Harris community?

I always have about five books going at any one time, and right now I’m in the thick of my research for my next book project. It’s a story about America’s most famous war correspondent from the Second World War. His name was Ernie Pyle, and I’m retracing his steps through the war to try to figure out how he wrote such impactful stories without upsetting readers at home or the military censors far behind the front lines.

As for recommendations, if you’re looking for other great books about writing, especially personal essays, you can’t go wrong with The Situation and the Story by Vivian Gornick, Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott, Writing Down the Bones by Natalie Goldberg, Draft No. 4 by John McPhee, and The Art and Craft of Feature Writing by William E. Blundell. None of those books are ever too far out of reach when I’m writing.

Where can I learn more?

On Wednesday, July 21st from 5:30-6:45 pm CST, Harris is hosting a panel to celebrate the publication of my book and to start a conversation about the role of storytelling in policymaking. I’ll be joined by Professor Gina Fedock, of the Crown School of Social Work, Policy, and Practice, whose work focuses on improving women’s mental health, and Dr. Brian Williams, a trauma surgeon at UChicago Medicine. We’re going to talk about some of the lessons in my book and how storytelling can be used to impact policy. I think it’s incredibly important, if we’re going to tell policy stories about trauma, that we first understand what trauma does to a person and then find ways of understanding our own stories. Then, when we’re working with others and hearing their stories, we can be much more thoughtful—and responsible—about how we share what we’ve learned so that we remain storytellers and not storytakers. In addition, you can visit my website: www.davidchrisinger.com, where you’ll find all sorts of great stuff, including a few excerpts from the book and information about future events.

And for those Harris students out there who are interested in learning even more about writing about trauma, I’ll be teaching a trauma-informed policy writing course during the winter quarter this next year. The focus will be on effectiveness and ethics, though we’ll also practice ways of telling our own stories and taking care of ourselves when working on traumatic topics.

***

by Billy Morgan

Assistant Director, Communications

wrmorgan@uchicago.edu

773.834.9123